MOST people in present-day Bangladesh, including myself, belong to the post-1971 generation. We have only heard and/or read about the war that saw the birth of our country in 1971; we did not see or experience the liberation war or the jubilation over the victory that followed.

Unfortunately, we have also not seen people of Bangladesh reaping the expected benefits that independence from foreign domination is supposed to provide. Liberty, equality and justice for which people of our land fought in 1971 are still a mirage on the distant horizon for most of us. What is more, our educational, social, economic, political and other critical institutions and government agencies have largely been destroyed over the years. And unsurprisingly, they have had very little to contribute to meeting people’s hopes and aspirations.

For a long time, a section of our politicians, academics, writers, public intellectuals and media personalities and influencers kept seeing and interpreting the events of the 1971 war and its legacy through the lens of their own political beliefs and identities. They used the ‘spirit of 1971’ and related terms such as muktijoddha (freedom fighter) and razakar (traitor) to create divisions among us. They conferred these terms — muktijoddha and razakar — on whomever they wished on the basis of their partisan biases and group affiliations.

A certain political party and its spinoff intellectuals seemed to have at their disposal a miracle machine that helped them make inside-out changes. The machine allowed them to turn a muktijoddha into a razakar and a razakar into a muktijoddha — all based on their arbitrary, politically-motivated judgments and intentions. They capitalized on the naivety and ignorance of the gullible among us and made the rest of us confused and lost in a quagmire of controversies. By perpetuating distrust and disunity among us, they weakened the fabric of our nation. Our country slid into a moral abyss of corruption, exploitation, abuse of power, erosion of trust and the debasement of ethical values.

Our job recruitment processes have been riddled with bribery, nepotism and party favouritism. Graduates who are otherwise qualified but with no substantial political linkages or connections, or are unable to pay bribes, have had little opportunity to enter suitable employment. The absence of much-needed values of diligence, honesty and meritocracy has driven our country to the brink of collapse.

In workplaces, honest and efficient people have been ignored, marginalised and excluded from the sphere of influence. Conversely, the corrupt and inefficient ones have been favoured, promoted and enabled to climb into positions of power. Sadly, often such practices have been draped in the spirit of the 1971 liberation war.

Our students (mostly from underprivileged backgrounds) go to colleges and universities to study and to build a bright future for themselves and for us all. Unfortunately, they are the worst victims of the unjust system that has been in place in our country for decades.

Until recently students in Bangladesh were mistreated at campuses and dormitories. They were beaten up for not attending political programmes and for not doing the bidding of ‘cadres’ (ruling party student thugs). We have a generation of students who have lived in fear at campuses and dormitories, and university administrations have hardly lifted a finger to come to their aid.

Our graduates face discrimination in the job market. Unemployed, they see their poor parents and other family members suffer starvation and hardships. Their inability to help their near ones has remained a source of frustration and face-hiding shame for them. Many of them eventually leave the country and do menial jobs in foreign lands. Again, at our airports they are vulnerable to harassment and extortion.

Stories of our follies and failures are unending. But what is pathetic is that most of our academics, writers and intellectuals have remained largely quiet about all such inequities and injustices. For example, in their journalistic pieces and media appearances, there is a big elephant in the room — the predicament of students at campuses and dormitories. They have not done enough to mitigate the sufferings of their own (underprivileged) students at the hands of the thugs of student organisations. Instead, some of them use their leverage mainly to access the corridors of power and advance their own selfish interests.

The vulnerability of our students to political oppression reached new heights during Sheikh Hasina’s 15-year long autocratic rule (2009–2024). Her so-called student organisation Chhatra League remained a dreaded name, and torture of ordinary students at the hands of its members became commonplace.

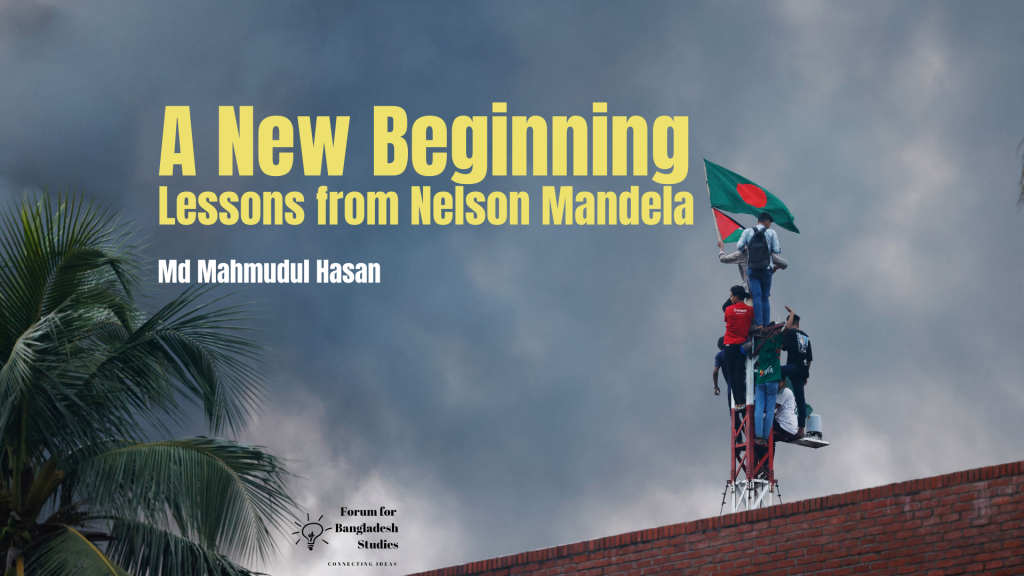

Students’ pent-up anger and frustration were bottled up inside them for a very long time. Having little support from their father-like teachers or others, they took their freedom from oppression and discrimination in their own hands. This heralded the glorious anti-discrimination student movement that resulted in the end of Sheikh Hasina’s despotic and blood-thirsty rule.

In the weeks leading to her resignation and cowardly flight from Bangladesh, Hasina launched a crackdown (mass slaughter) which resulted in the death of over four hundred young people in the span of a couple of weeks. Thousands of bullet-hit young people are still in excruciating pain in hospitals and some are still succumbing to injuries.

After decades-long suffering of the people of Bangladesh, Hasina’s fall from power marks a new beginning for Bangladesh.

Against this backdrop, it is important to discuss our failings in post-1971 Bangladesh and what we can learn from Nelson Mandela’s rule of post-apartheid South Africa. This may help us make post-Hasina Bangladesh a success, not a repetition of post-1971 follies and failures.

After taking his oath as the president of South Africa in 1994, Mandela said this to a jubilant crowd:

‘We enter into a covenant, that we shall build a society in which all South Africans, both black and white, will be able to walk tall, without any fear in their hearts, assured of their inalienable right to human dignity — a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world… Never, never, never again shall it be that this beautiful land will again experience the oppression of one by another, and suffer the indignity of being the skunk of the world.’

In apartheid South Africa, the indigenous black majority suffered unspeakable horror and atrocities at the hands of the settler white supremacist minority. Once apartheid rule was over, Mandela sought to protect the rights of both black and white populations and prevent a relapse into old discriminatory practices.

In post-1971 Bangladesh, we failed to adhere to the virtues of benevolence, magnanimity and altruistic sentiment. Duped or driven by vested interests, a section of our intellectual elite spent much effort sowing divisions among us. In post-Hasina Bangladesh, let us remember Mandela’s words and make a strong resolve to foster unity among us. We should begin with promoting decency, fairness and justice in conducting our affairs. Importantly, we must be vigilant so that Hasina-style misrule can visit our land never again.

Originally Published: New Age, August 11, 2024,